zero kids later ii

this is the second part of the series. you don’t need to read part i to understand it and part iii is here.

“remember kids: remember your parents.” — rz

“the days are long while the years are short.” — whoknows

my parents have accomplished remarkable things. they have much to be proud of.

they have many prides that don’t have anything to do with family, and yet, the thing that makes my parents proudest is scary to me: it’s my sister and me. i’m fine with their being proud of my sister. but me? terrifying. lots to live up to.

they're not shallow or unaccomplished, either. to make the point, let me tell you their story. it is an immigrant story, but that part starts way later than i'd guess.

you think your friends at the mercy of the H1B visas have it hard? well, they do. but:

try being an immigrant in your 40s, from the 2nd poorest country in Latin America, where you have lived all your life, without speaking the language (Korean), with two college-aged kids already studying in the US, and in a rocky marriage. to serve the situation its due justice would take us way too far into the murky waters of sociopolitical dysfunction otherwise known as Bolivian society. let it suffice to say that immigrating was a necessity, just shy of a sufficiently-dire one to be considered for asylum.

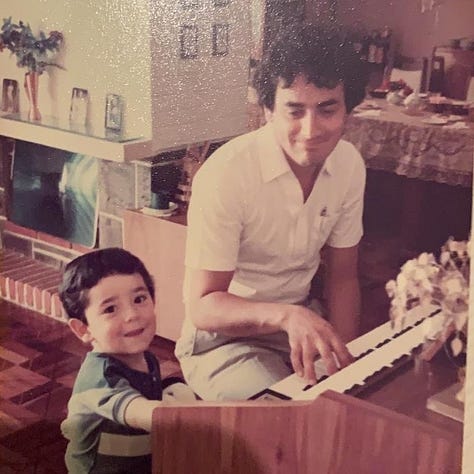

first, my dad. he is as accomplished as a pilot can be.

Claude informs me that the typical number of flight hours for an airline pilot in their mid-40s is ~10k. by age 46, my dad had logged 15k flight hours and well over half were in the lefthand seat (ie as captain). he’d flown F27s, B707s, B727s, A320s, B767s, and probably others. he recently retired from flying after another unblemished long run flying B777s at Emirates, known in the industry for its exacting crew performance standards (and also on insta for their luxe first-class cabins :).

he’s not only an accomplished pilot, though. before leaving, my dad held various executive roles in Bolivia’s then-flagship airline, LAB, which stands for Lloyd Aéreo Boliviano aka “El Lloyd”. being an exec ultimately led to needing to immigrate.

you see, El Lloyd was state-owned and operated for its first 70 years and subsequently privatized. and a lot of people had politics about that. what’s more, the airline was a mess in the latter years of state-ownership, and my dad was among the executives tasked with cleaning the mess when it became private. alas, the mess proved messier than their efforts at cleanup proved workable. to be fair, there was also nepotism, power dynamics, and national politics.

it was to escape all that that my dad’s immigrant story began.

what about my mom?

her story is decidedly intertwined with my dad’s, but it is also remarkable in her own right.

my mom gave up her whole career to care for me when i arrived. she was a promising young lawyer and also set to take over her dad’s pharmaceutical distribution business, all while helping run the family bakery, and having started a bar with her sister during college.

their bar, “El Buca” (nickname for “Le Boucanier”), as we knew it posthumously, was reportedly a tiny room, where two stylish ladies improvised cocktails for the clientele, while far too many people crammed in to make a scene. it must’ve been such a vibe. Studio 54? pft. El Buca was the premier place to be in Cochabamba in the late 1970s. hey, it’s a poor small country, okay? we make more do with less done.

this cocktail was stirred and had an interesting twist: during those years, the dictatorship had imposed martial law and a nighttime curfew of 11pm. my mom even knew someone who was shot & killed by the military while crossing a bridge on motorcycle past curfew.

the sisters’ MO was to kick out the last few drunks from El Buca as close to 11 as possible and then b-line it on foot from “La 25 de Mayo entre Ecuador y Colombia” to their house in “La Recoleta” — a 20min walk involving the bridge.

there’s much family folklore about the games of avoidance they played against the troops which is enhanced by the fact that all houses in Cochabamba sit behind tall walls and ornate iron gates. fortunately for the sisters, the fashion of the time didn’t call for dresses — though my mom’s sister was an early trend-setter for the long midi skirt.

my mom and her sister were pretty popular in town, without insta or tiktok. it wasn’t that they were popular because of El Buca, it was the other way around.

this is all to say that when i came to being, well… everyone was a little surprised. some friends even staged an intervention to talk sense into my mom about how she had become less ambitious.

friends, it wasn’t that she became less ambitious. it was that her ambitions changed.

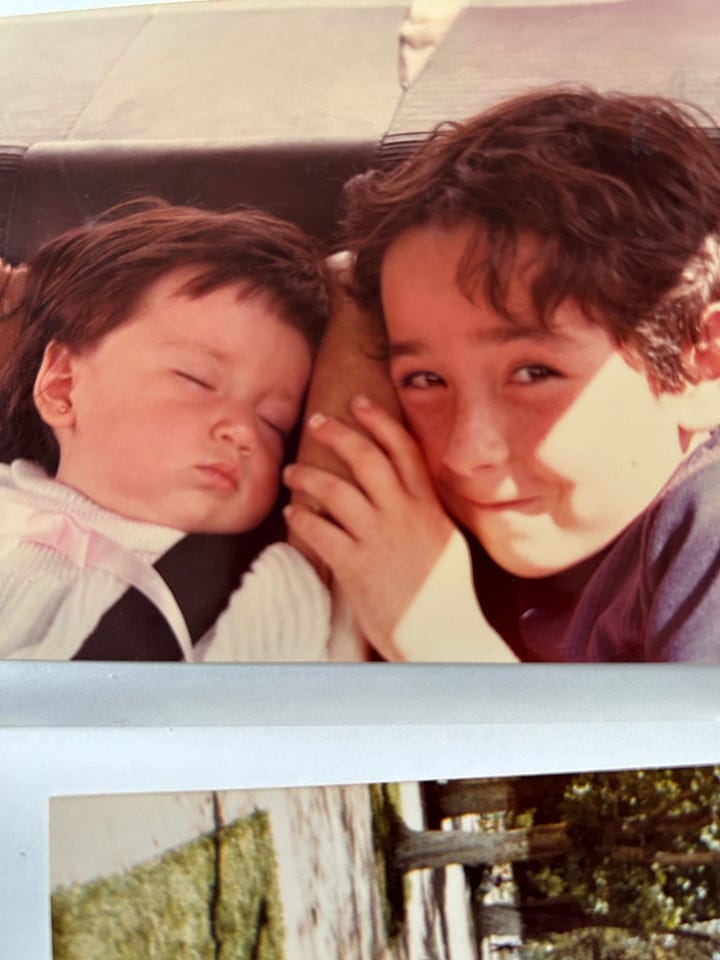

my mom then worked as a bank teller when i was a baby, but gave that up after a couple of years to focus on making the happiest possible home out of a crappy set of ingredients. i won’t go into the details, but let’s say that three of the ingredients were the first of my parents’ two divorces, Bolivia’s hyperinflation and political instability in the early 80s, and that her parents were not supportive of her one bit. she was on her own, though she did accept help from my dad’s parents — my mom and me lived with her ex-inlaws for a while. crappy ingredients, yeah?

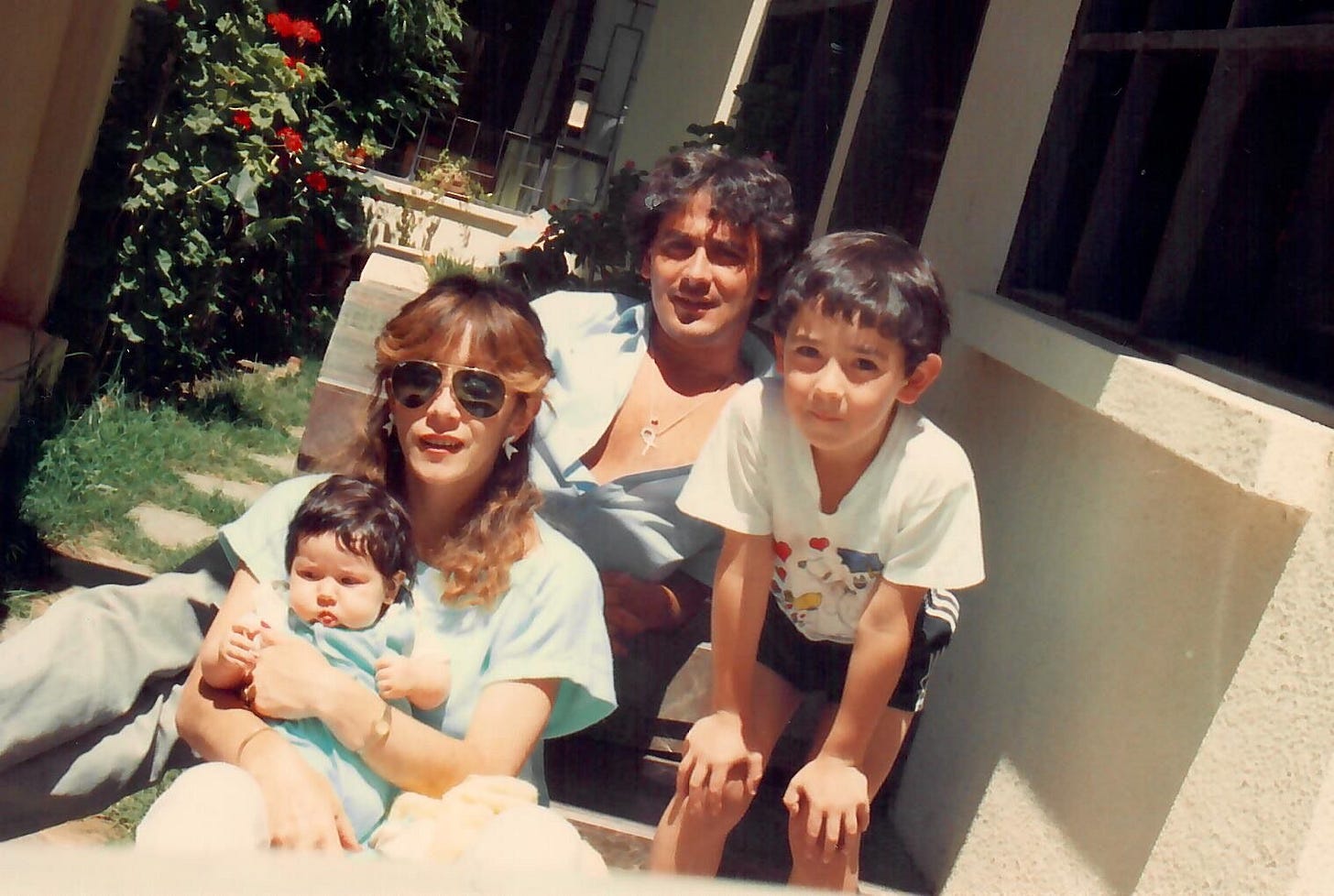

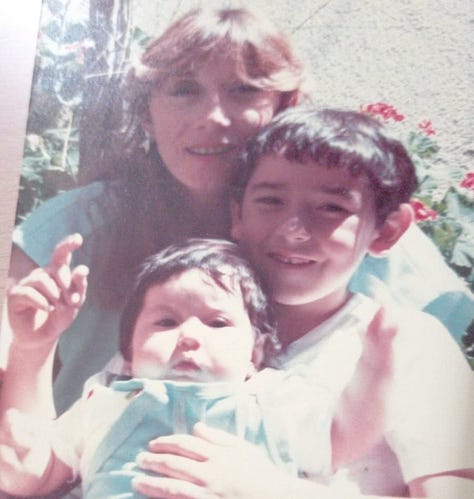

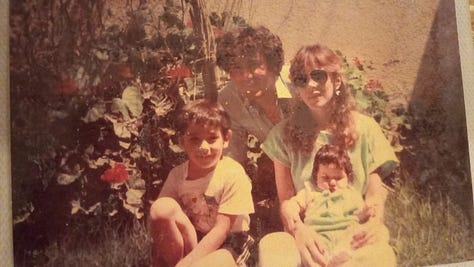

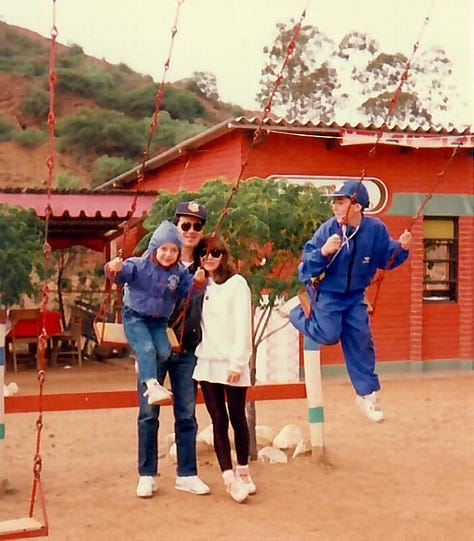

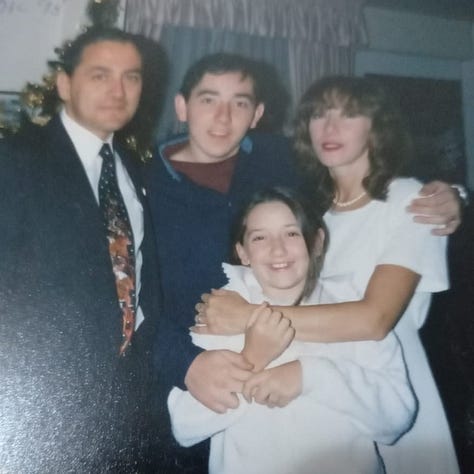

my sister came about 6 years after me, after my parents had separated, divorced, remarried, and moved into La Casa, the house we grew up in. that’s when my mom really started succeeding at this happy home thing.

our family life in Bolivia wasn’t exactly a walk in the park and money got tight sometimes, but we were reasonably well-off (in Bolivian money). my dad was gone a lot (pilot) and later, when he became an executive, his work became very stressful. even as an exec he had to fly a minimum number of hours to keep his license current. so, my dad was stressed out and gone a lot.

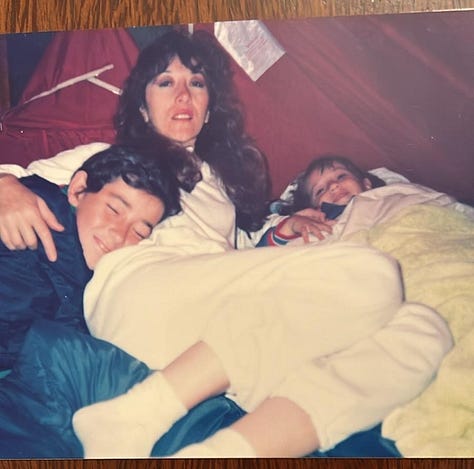

what did my mom manage to make out of gone-ness, stress, and rocky relationship fundamentals? the happiest home for my sister and me.

surely my dad deserves a line or six in the credits, but i think he’d agree that the happy home was directed and produced by mom. my dad’s parents, El Abuelo Roger y La Abueli Zorki, present and helpful throughout, were very influential and also deserve lines in the credits. my mom’s parents, El Espada y La Charo, made credited appearances in latter years.

all this added up to my sister and me not even noticing that dad was gone per se, it was more like we had a happy life in the home of a pilot and his wife. after i learned the phrase in college, i’d describe us as a cereal-box family. i only learned about my parents’ relationship troubles much later in life.

i didn’t make anything of it at the time (worked as intended), but now as an adult, i have nothing short of admiration for that happy home. heck, i’m happy with myself when pasta comes out tasty. dishes? wat? no. later. today pasta good. tomorrow dishes maybe.

no really, think about it: you probably have some sentiment along the lines of “adulting is hard”. and well, yeah, it is. doing laundry AND my taxes this week? heavens! who has that kind of emotional bandwidth?!?

yet, if you ask my mom whether it was hard to create the happy home, she’ll say no. sure, it had emotional and logistical challenges, but the fact that it was all for my sister & me kept the priorities straight, and made it enjoyable and actualizing. and ask her, i have. the report reads “enjoyable and actualizing”, “happiest years of her life”.

it is fair to say that my mom gave up her career in order to be a stay at home mom. she’s happy to have done so. and i suspect she didn’t think, ahead of time, that she’d turn out feeling that way.

having kids changes you. further, i venture it changes you for the better. if you can, ask your parents about it.

my parents’ transformation made my sister and me, and we’re nothing short of immensely grateful for that.

after the decades of happy home, life moved forward, i went to college in the US, and then so did my sister, El Lloyd imploded, and my parents left Bolivia for South Korea.

it was to keep trying with my dad that my mom’s immigrant story began.

Korea only lasted a couple of years before they re-immigrated, this time to Dubai, for my dad to work at Emirates. they faced expected immigrant trials & tribulations. they also faced other trials which eventually led to their second divorce. my mom went back to Bolivia after that. my dad worked at Emirates until retirement and is currently an instructor for Cathay Pacific.

you see? lawyer. B777 captain at the most prestigious airline in the world. multiple-time scrappy business owner. international airline pilot instructor. kinda impressive, yeah?

and yet… and yet, at basically every time scale (after a year, 5, 10, 20, 40…) they report infinite happiness at having had kids and centering their lives around that. what’s more, centering their lives around that didn’t keep them from their accomplishments. starting a family is, well, starting…it’s a beginning, not an ending.

my parents are far from outliers in having this perspective. it’s the same when i look around my own circle of accomplished friends and acquaintances — professors, artists, investors, startup founders, multiple who are more than one of those things, and more. the thing that surprises me the least now (but might’ve surprised me a lot earlier) is that in that sea of accomplishments, everyone who has a family is the proudest of that, their family. yes, despite the career tradeoffs and peak-diaper season.

i considered asking actual-parent friends for actual-testimonials, but that’d belabor the point too much. everyone reports basically the same thing: they are very happy they oriented their life around having kids and subsequently had the kids. yes, it came with work and diapers, but the days are long while the years are short.

the days are long while the years are short.

becoming a parent changes you deeply and for the better.

and it’s not only my friends & family who say this. for example, here’s Emmett recently, earlier, and earlier:

There are a lot of things people say about the importance of their kids and their spouses that sound a little over the top until you experience it for real.

I’m grateful today for my family. We are all born with a family, but having a child I get to be part of creating the family. I didn’t quite realize how meaningful that would be, and I’m so grateful to have this chance on earth.

Raising children and running a family well is one of the most scalable impacts you can have tho?

and there’s also that one pg essay on the subject (worth reading the whole thing):

Before I had kids, I was afraid of having kids. […]

[…]

When people had babies, I congratulated them enthusiastically, because that seemed to be what one did. But I didn't feel it at all. "Better you than me," I was thinking.

Now when people have babies I congratulate them enthusiastically and I mean it. Especially the first one. I feel like they just got the best gift in the world.

What changed, of course, is that I had kids. Something I dreaded turned out to be wonderful.

so, to my reading, the actual-testimonials from actual-parents say that having kids changes you and changes you for the better.

when i ask my parents, on the other side of all their stories, what are they proudest of? yeah…my sister and me.

you might be tempted to think that my parents want to maintain the illusion for our sake. yeah, maybe. i used to think that, actually. i don’t think that any more because of how consistent their expression is with that of my closest friends who are parents. i now simply believe all of them, my parents included, when they say they are proudest of their families.

so. much. to. live. up. to.